|

The other Punjab

Nadeem F Paracha

The other Punjab

NADEEM F. PARACHA

Ever since Pakistan’s tumultuous birth in 1947, much has been said and written about the topic of ethnic nationalism(s) in the country. This has always been a thorny and controversial subject because elements advocating the importance of exhibiting nationalism based on the linguistic and cultural injunctions of an ethnic community have always been dealt with suspicion by the state of Pakistan.

|

Illustration by Abro |

If we keep aside the fact that more than 97 per cent of Pakistan’s population is Muslim, this same population is then not a homogenous lot. In fact, even within its religious homogeneity there are sectarian, sub-sectarian and intra-sectarian divisions, with some of the various groups rather antagonistic towards one another.

Pakistan is made up of various ethnic groups that have their own languages, historical trajectories, and cultural traditions. Picturing such a diversity as a threat (to the unity of the country), the state of Pakistan, right from the word go, has launched various projects to concoct ideas of a unified nationalism to overcome and neutralise identities based on ethnic moorings.

Punjabi nationalism over the years

Naturally, such projects have created tensions between the state and various ethno-nationalist groups who accuse the state of Pakistan of trying to whitewash their centuries-old ethnic heritages with (what these groups believe is) an ‘artificial ideology’ invented by the state.

What’s more, the antagonistic ethno-nationalist groups have for long maintained that the state enforces such an ideology to safeguard the political and economic interests of the ‘dominant ethnic communities’.

Till the late 1960s the so-called dominant ethnic groups were supposed to be the Punjabis and the Urdu-speakers (Mohajirs) who had a monopolistic influence on the workings of the armed forces, the bureaucracy and large economic enterprises (and thus politics).

In this scenario ethno-nationalism in Pakistan was thus mostly the vocation of non-Punjabi and non-Mohajir ethnic groups, mainly Bengali, Sindhi, Pakhtun and Baloch.

According to the narrative weaved by some prominent Sindhi and Baloch ethno-nationalists, after the separation of the Bengali-majority East Pakistan in 1971, the state began to gradually co-opt the Pakhtuns who then began to replace the Mohajirs as the other dominant ethnic elite (along with the Punjabis).

By the 1980s Pakhtun nationalists had lost considerable appeal among the Pakhtuns but the same decade saw the emergence of ‘Mohajir nationalism’.

Ethno-nationalists have continued to accuse the ‘Punjabi-dominated state’ of usurping the economic and political interests of the non-Punjabi communities, sometimes in the name of Pakistani nationalism and sometimes in the name of religion.

Academics studying the phenomenon of ethno-nationalism in Pakistan usually stick to tendencies such as Sindhi, Baloch and Pakhtun nationalisms (and, in the past, Bengali nationalism, and now even Mohajir nationalism).

Nevertheless, what gets missed in the more holistic study of the said issue is a nationalism that is actually associated with what is usually decried to be a hegemonic and elitist ethnic group: the Punjabi.

This is not due to there being not enough activism and literature available on ‘Punjabi nationalism’ as there is on other ethno-nationalist tendencies in the country.

The Punjabis have for so long been seen as the dominant ethnic group, very few scholars have actually got down to study curious occurrences such as Punjabi nationalism.

Also, compared to other ethno-nationalisms in Pakistan, Punjabi nationalism is a more recent phenomenon.

According to cultural historian, Alyssa Ayres (in her book, Speaking Like A State), Punjabi nationalism largely emerged in the 1980s. Part of it was a reaction to the emergence of the Saraiki language movement that looked to separate the Saraiki-speaking areas of the Punjab from the rest of the province.

Till the late 1960s, Saraiki was considered to be a dialect of Punjabi, but Saraiki nationalists disagree and treat their language as a separate linguistic entity.

Ayres suggests that many Punjabi intellectuals considered the Saraiki movement as ‘yet another attack on Punjabi.’ They bemoan the way Punjab as a whole has been lumped together as a hegemonic province. They complain that a Punjabi actually has to let go of his culture and adopt ‘alien languages’ (English and Urdu), if he wants to escape economic marginalisation.

Just as the purveyors of Sindhi, Baloch and Pakhtun nationalism of yore, ideologues and advocates of Punjabi nationalism too emerged from progressive backgrounds.

They did not attack the non-Punjabi ethnicities for denouncing Punjabis; instead, they turned in anger towards the elite sections made up of fellow Punjabis. They accused them of neglecting the Punjabi language and forgetting the Punjabi culture — first to appease the British, and then to the state-backed promoters of Urdu — just to maintain their personal influence and power.

Though literature in this context had begun to trickle out in the 1970s, it was the publication of three books between 1985 and 1996 that finally gave Punjabi nationalism its most cohesive literary shape.

The first was Hanif Ramey’s Punjab Ka Muqadma (The Case of Punjab). Ramay was a founding member of the PPP; and a leading ideologue behind the party’s populist concoction called ‘Islamic Socialism’ (late 1960s).

In his 1985 book, Ramay suggests that the Punjabis turned against the Bengalis to safeguard the interests of those who had imposed Urdu (‘a foreign language’) upon them (the Punjabis).

Ramay continues by claiming that had the Punjabis continued to respect and love their own language, they would have understood the sentiments of East Pakistan’s Bengalis, and would not have turned against them.

The book was promptly banned by the intransigent Zia regime.

The ban did not deter Syed Ahmed Ferani from authoring Punjabi Zaban Marre Gi Nahi (The Punjabi Language Will Not Die) in 1988. This is an even more radical expression of Punjabi nationalism. Here Ferani describes Urdu as ‘a man-eating language’ that made Punjabis kill fellow Punjabis and then people of other non-Urdu ethnic groups. This book too was banned.

The third major work in this context is a novel authored by Fakhar Zaman called Bewatna (Stateless) in 1995. Zaman, another former PPP man in Punjab, wrote an allegorical lament about how (he thought) the Punjabis (by adopting alien languages and cultures) have become aliens on their own soil. The novel, too, was banned.

Unlike certain more radical branches of non-Punjabi ethno-nationalisms, Punjabi nationalism (so far) has not been separatist and has remained largely a literary pursuit, only calling for the Punjabi language to be given its rightful place.

This nationalism’s scholars constantly evoke tales associated with various Punjabi Sufi saints and anti-colonial heroes to emphasise the point that the Punjabi culture was spiritual (instead of orthodox) and chivalrous (instead of hegemonic or exploitative).

In a landmark decision, the Lahore High Court (in 1996), overturned and lifted the ban on all three books.

Echoes of this nationalism can still be heard in the Punjab, though. In a TV talk show about three months ago, the current Defence Minister and a senior member of the ruling PMLN, Khawaja Asif (who hails from the Punjab city of Sialkot), lamented that all kinds of ‘alien cultures’ have been imposed in the Punjab.

He specifically mentioned the erosion of Punjab’s original culture and traditions that were being replaced by a culture imported by those (including fellow Punjabis) who have for long resided in Arab countries.

And though Khawaja Asif never called himself a Punjabi nationalist, his lament did bear the tone first set by Punjabi nationalists.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, Sunday Magazine, May 31st, 2015

Punjab khappay?

NADEEM F. PARACHA

According to many emails that I received after posting a blog in the wake of the terrible bomb attacks in Lahore last week, I was ‘spreading politics of ethnicity.’

I don’t know exactly what made these folks think this way, but the accusation does smack of an attitude demonstrated by many of my fellow countrymen when they are asked certain thorny questions regarding ideology and religion: they at once either label the questioner as being ‘anti-Islam’ or ‘anti-Pakistan.’

I am not the only writer in this country who has faced this kind of a barrage, mind you. Men and women like Dr. Pervz Hoodbhoy, Ahmed Rashid, Asma Jehanjgir, and late Akhtar Hamid Khan have had their share of such laminating labels bestowed upon them long before others like Hassan Nisar, Imtiaz Alam, Fasi Zaka, Irfan Hussain, Ayesha Siddiqua, Hassan Askari, Nazir Najee, Kamran Shafi, and myself became the Islamic Republic’s new batch of anti-Pakistan/anti-Islam devils.

Ironically, just what I meant in the blog, ‘Wake up, Punjab,’ was blatantly proven by the recent comments by Punjab’s Chief Minister and the president of the province’s ruling party, the PMLN, Shahbaz Sharif. Not only did the man conjoin the anti-Americanism of the Taliban with that of his own party, but he also pleaded for mercy from the terrorists specifically for his home province of the Punjab.

Why does Mr. Sharif want the Taliban to only spare the Punjab? Isn’t the Taliban issue a national menace that has affected the whole country? Sharif apologists defend his stance by suggesting that since Shahbaz Sharif is the Chief Minister of Punjab, he is likely to only talk about the Punjab.

If so, then Mr. Sharif and PMLN members from the Punjab should stick to their province, instead of dishing out the lofty tirades and sermons that they love to deliver on the corruption of President Zardari and the incompetence’ of the current PPP-ANP-MQM coalition governments in Islamabad and in other provinces.

Even if one gives Shahbaz the benefit of the doubt that he spoke strictly as the Chief Minister of the Punjab, how is one to explain his weak-kneed attitude towards the Taliban – an organisation which, along with its many clandestine foot soldiers in shape of assorted sectarian outfits, has been responsible for literally slaughtering thousands of common men, women and children in the mosques and bazaars of Pakistan.

These are monsters against which the military, political parties, and a majority of Pakistanis are fighting a deadly battle, losing numerous lives, both uniformed and civilian, in the process.

How can one explain Shahbaz’s insistence that the Taliban should spare the Punjab because the ‘PMLN too is anti-American.’ Was he suggesting that the PMLN endorses the Taliban ideology? An ideology of utter bloodshed, remorseless violence, coercion, and theological psychosis cloaked with rhetorical anti-Americanism and a demand for Sharia law? An ideology both the state and society of Pakistan have been at war with for the past five years of so?

What does Mr. Sharif mean by ‘anti-Americanism?’ How is his party any different from the parties the PMLN accuses of being ‘American stooges?’ Any high-profile official of American or western states who visits Pakistan is also met by PMLN chief Mian Nawaz Sharif. Why can’t he just shun them?

And how is ‘American interference’ that parties like the PMLN and Jamaat-e-Islami are always lamenting any different from Saudi interference? It was the US along with the Saudis who were the biggest donors to the anti-Soviet Afghan ‘jihad’ in the 1980s. What’s more, the Saudis were also the only other country (apart from, of course, Pakistan) that actually recognised the brutal tyranny of the Taliban under Mullah Omar and Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan (1996-2001).

Today, after facing the wrath and the madness of the monsters that it helped Pakistan create, the Saudis are willing partners of the US in its war against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. So how come not a word is uttered by the PML-N against the Saudis as well?

Effective politics is first and foremost about policies derived from diplomacy and pragmatism and then implemented through a democratic consensus. Ideology works merely as a cover to communicate such policies on a populist level. There’s a lesson to be learned here by Shahbaz Sharif and the PML-N. PML-N’s popularity in central and upper Punjab is still rooted in the solid developmental work it did in that province between 1985 and 2007.

Its weakest link, however, has remained its ideology. Unfortunately, no matter how hard it has tried to sound like a national party, the PMLN’s ideology always seems to be stemming from the ethos of Punjab’s conservative sections. This ethos is the one that also informs the ideological make-up of the Pakistan Army and large sections of the province’s bourgeois and petty-bourgeois classes.

Over the decades it has been accused by Sindhi, Pushtun and Baloch nationalists of dictating (through the ‘establishment’ and the military) a homogeneous Pakistani nationalism, but one that is ingrained in the Punjabi industrial, bureaucratic and political elite’s worldview.

And therein lies PMLN’s ideological dilemma. This worldview is a strange brew of aggressive anti-India positioning; a scorning disregard for any attempt to give Sindh, Pakhtunkwah and Balochistan any worthy degree of political autonomy; an air-tight notion of political and cultural Islam that attempts to overwhelm the many other strains of the faith that exist in the country; and a stringent observance of public conservatism. Add to all this a new-found respect for democracy and claims of anti-Americanism and you have in your hands the ideology of the PMLN.

However, if you slightly alter this, wouldn’t one then get what, say, a reactionary political party like the Jamaat-i-Islami stands for?

Yes. But the difference is the PMLN’s legacy as a doer party. It is this and not entirely its ideology that is helping it bag votes in the Punjab. It is the doing bit that gets votes for other mainstream parties as well such as the PPP, ANP and the MQM.

Nevertheless, whereas the other parties mentioned have been pragmatic and progressive enough to let their ideologies evolve according to the needs of the time, the PMLN seems to be getting stuck in an ideological hole that it continues to dig for itself.

One moment it is quick to show off its new-found credentials as a modern democratic party working for the rule of law and constitutionalism; the very next moment one is baffled by the way this party continues to romanticise ideas and entities associated with the most reactionary strains of Islam.

For example, the PMLN is quick to make sure Lahore’s traditional festival, Basant, is banned because many people lose their lives. If so, many people also lose their lives during Ramadan. According to a research, the number of traffic accidents almost double every Ramadan about half an hour before the opening of the fast as motorists and bikers try to hurry back home. Does this mean that Ramadan too should be banned?

The PMLN government was even quicker to put restrictions on Punjab’s once thriving popular theatre scene and on the late night packages offered by telecom companies because they are ‘a bad influence on the youth.’

Meanwhile, Punjab Law Minister, Rana Sannullah, is seen (literally) holding hands with the chief of a banned sectarian organisation, and Shahbaz Sharif says his party’s ideology is close to that of the Taliban. Is this meant to imply that terrorists are a better influence on the youth? Is a suicide bomber exploding himself in public a better influence on the youth than a dance performance by Nargis on a Lahore stage?

Ban the theatre actors and dancers, curb night-time offers from telecom companies, put a stop to men wearing shorts in public (I’m serious), let hate-mongers make whirlwind tours of Lahore’s educational institutions, keep badmouthing the president, but at the same time sound meek, hopeless and even reconciliatory when it comes to brutal terrorists. Is this the PMLN’s idea of a ‘sovereign,’ just and democratic Pakistan?

Spurred on by one particular TV channel which itself has kept its own historical skeletons locked in the closet while lecturing the nation on sovereignty and a corruption-free Pakistan, the PMLN has begun to perform not for the people as such, but for TV audiences. And that is dangerous.

The PMLN’s growing self-righteousness that sounds so pleasant on TV cannot continue to get it votes. As mentioned before, it is the party’s legacy of being a resourceful political entity that can actually undertake developmental work that matters.

And come to think of it, it is easy to criticise the current PPP-led coalition government for struggling against the Taliban menace. But the truth is, the real failure in this respect is more obvious in the Punjab than anywhere else.

The Punjab government and those who support it should seriously start to rethink their priorities. Again, one of the easiest (if not also the laziest) things to do is to sound all lofty, high and mighty talking about sovereignty, independent judiciary, corruption, et al, on the TV; but all this starts to seem dizzying and fluff-like in the midst of loud, rude bomb attacks by men who are a million times worse than what the PMLN is so concerned about.

In parting, I would also like to sincerely advise the doings of certain TV channels whose policies are clearly echoing those of the PMLN. On these channels, amidst sounds and visuals of gory suicide attacks, death and destruction, one can still catch sheer hate-mongers masquerading as preachers, ‘scholars,’ talk show hosts and ‘security analysts.’

My question to these channels is, if you think that corruption and lack of accountability are not good for the country, then how good are those we see sprouting utter hatred and mischief in your studios? And anyway, accountability, like charity, should begin at home, shouldn’t it?

CURTSEY:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED MAR 16, 2010 06:18PM

Wake up, Punjab

NADEEM F. PARACHA

Another bomb attack in Lahore. What to expect from the PMLN government in the Punjab? Lip service condemning terrorism, of course. But, as usual, keeping in mind the Punjab government’s past record, the condemnation will be general and vague.

Even as the PPP-led coalition government in Islamabad will not hesitate to take names – they’ll point to the Taliban or the many sectarian organisations working as Al Qaeda’s foot soldiers – it is expected that the Punjab government under the PMLN will not.

Determining which forces are hell-bent on mutilating the country is not rocket science. But brace yourself (yet again) to be bombarded by the PMLN leadership and the usual intransigent suspects on TV channels talking generalised nonsense about terrorism and the ubiquitous ‘foreign hand,’ consequently drowning out the obvious involvement of any of the many extremist organisations running amok in Pakistan’s largest province.

But why the Punjab? Although it has been ravaged and broken by extremist terrorism for over two years now, political parties strong in the Punjab (such as the PMLN), the Punjabi-dominant electronic media, and fringe Punjab-based politicos such as Imran Khan have simply refused to acknowledge reality.

Still operating from the fanciful high pedestal of a superiority complex, a bulk of urban Punjab and its leadership continues to live in a stunning, air-tight state of denial.

Whereas in Karachi one can find a majority of common men and women unafraid to air their distaste for the extremists, and walls can be seen adorned with slogans such as ‘Taliban raj namanzoor’ (Taliban regime not acceptable), ‘Taliban sey hoshiar’ (beware of the Taliban), and, my favourite, a slogan found scribbled in a thick coat of black on a wall in a rundown lower-middle-class area of the city, ‘Mulla Omar dajjal’ (Mulla Omar the devil), one just cannot expect such voices and scenes in the Punjab, at least not in Lahore.

Why not? How can a province and a city (Lahore), devastated over and again and plunged into the depths of chaos and fear perpetrated by monsters such as the Taliban, Al Qaeda, and the province’s many clandestine sectarian organisations, simply refuse to face its most ubiquitous tormenters and demons? Why the fearful silence by its people, and why the spin, the vagueness, and ultimate derailing of the issue by the electronic media?

Punjab is suffering. And it is not only from extremist terrorism. It is as if every time its leadership and people attempt to awkwardly repress the obvious lashings of fear and confusion that cut viciously across the province whenever there is a terrorist attack, they become more vocal in their condemnation of the present government at the centre, incredibly investing more emotional and intellectual energy on abstract issues such as corruption, judiciary, and ‘good governance’ through passionate displays of TV studio and drawing-room nobility, rather than directly tackling their greatest enemy.

Funny thing is, they would readily accuse the president of corruption and the US and India for having nefarious designs on Pakistan without offering an iota of evidence, but would get into a long navel-gazing exercise asking for proof of militant involvement in a terrorist attack.

Again, why? Why in the Punjab? Are the Sindhis and Karachiites more enlightened, liberal, moderate or whatever? Some of my most intelligent friends are from the Punjab, as was my father. And so I keep asking these friends, why isn’t the Punjab fighting back this menace of extremism? Why have most of this province’s brightest minds allowed themselves to be pushed in the background by this new breed of neoconservative ‘intellectuals’ in the shape of TV talk show hosts, ‘journalists,’ ‘analysts,’ et al?

I will continue by relating two small but relevant incidents that may help clarify what I am rambling about.

In a province that has been witnessing nauseating bloodshed perpetrated by those who have a painfully narrow view of Islam and are least hesitant to slaughter innocent men, women and children in their pursuit of both heaven and the shariah, one of the Punjab’s leading politicians and ministers did not find anything wrong in accompanying the leader of a banned sectarian organisation during a recent election campaign.

The minister was PMLN’s Rana Sanaullah, who proudly stood beside a notorious leader of a banned sectarian organisation during a by-election rally in Jhang. This organisation openly sympathises with the Taliban.

Only in the Punjab can such an episode take place. Only in the Punjab can a minister can get away with holding hands with a myopic violent fanatic and, in the process, openly mocking and insulting the feelings of hundreds of Punjabis whose loved ones were brutally slaughtered by the extremists that the fanatic sympathises with. Only in the Punjab can his party then go around and ask for votes from the same people. Yes, only in the Punjab.

One can also mention a recent incident that involves Zaid Hamid to hit home the point I am trying to make.

Mr. Hamid, a hyperbolic TV personality who is an animated cross between a foaming televangelist and an impassionate right-wing drawing room revolutionary, has been on a ‘speaking tour’ of various colleges and universities of the country.

Known for openly holding (and advocating) gun-loving militarist hogwash, Hamid has turned distorting history and dishing out the most twisted conspiracy theories not only into an attractive art form, but a lucrative undertaking as well.

Hailed as a modern Saladin (of the armchair variety, I’m afraid) by his mostly urban, middle-class fans, and flogged as a hate-monger with links to the most rabidly anti-India and reactionary sections of Pakistan’s intelligence agencies by his many detractors, it has been very easy for Hamid to speak at Lahore’s private universities and colleges.

This included a visit to the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) that only two years ago was the scene of a lively students’ movement against the dictatorship of General Pervez Musharraf.

If the student body of the prestigious university found Musharraf’s action of dismissing a chief justice unbearable, I wonder what was so bearable about a man who is not only a self-claimed supporter of the ex-dictator, but also a proud war monger whose fans are famous of uttering insightful gems such as “if the Pakistan Army was really guilty of raping Bengali women in former East Pakistan, then they had every right to because Bengalis were traitors!”

Nonetheless, after smoothly completing his ‘Wake up, Pakistan’ speaking tour of Punjab’s campuses, Hamid and his entourage of trendy, designer reactionaries, made their way towards the country’s most ravaged province, the Pakhtunkhwa.

Faced by an insane spate of suicide and bomb attacks by extremists and the military’s war against the Taliban, the youth of the Pakhtunkwa province have shown great resolve to fight back. Student organisations in various state-run universities and colleges of the province have gone on to organise cultural functions that the extremists would term ‘haraam’ and ‘unIslamic.’

Just like the Baloch Students Organisation (BSO) in Balochistan, the Peoples Students Federation (PSF), and the All Pakistan Muttahidda Students Organisation (APMSO) in Sindh, students’ organizations of the Pakhtunkhwa have continued to fight a cultural war against extremism, even when a recent cultural function organised at a university by the BSO in Balochistan’s Khuzdar area was bombed by extremists.

So when Hamid and his army of patriots reached Peshawar University, he was confronted by loud groups of protesting students who wanted him banished from the campus.

The protest, perhaps the first of its kind faced by the likes of Hamid, was organised by the Peoples Students Federation (the student-wing of the Pakistan Peoples Party), the Pakhtun Students Federation (the student-wing of the Awami National Party), and the independent collection of liberal students under the Aman Tehreek umbrella. What’s more, also joining in the protest was the Islami Jamiat Taliba, a student organisation whose mother party, the Jamaat-i-Islami, ironically sympathises with the Taliban.

As the students threw stones at Hamid’s entourage and tried to chase him off the campus, the Aman Tehreek explained exactly why democratic student organisations had joined hands to throw him out.

“We have already suffered a lot due to the suicide bombers and militants and do not want people (in our city and campuses) who promote the extremists,” said an Aman Tehreek activist talking to Dawn.

In light of this example, it seems Punjab’s political leadership is out of sync with the prevailing psyche in Sindh, Balochistan, and the Pakhtunkhwa regarding Pakistan’s war against extremism.

The people and politicians of Punjab need to contemplate difficult questions before they can rid their province of the violence that it has had to face. More so, the confused mindset that is causing violence to be bred and sustained in the Punjab must be eliminated.

CURTSEY: DAWN.COM PUBLISHED MAR 08, 2010

Punjab's Faith factory

NADEEM F. PARACHA

Last year, while on a visit to Lahore I had to meet an industrialist at one of his factories.The discussion between us soon drifted towards politics. Just two days before our meeting, there had been a deadly suicide bomb attack in Lahore.

It was the (thirty-something and well-dressed) gentleman who began the proceedings, but he soon said something that left me scratching my head. He asked (in Punjabi),

‘So Paracha sahib, has the situation in Karachi gotten any better?’

After realising that his question was not tongue-in-cheek, I wondered what on earth he was talking about.

Here was a man surrounded by frequent sights and sounds of devastation inflicted by rabid groups of extremists on politicians, military men, police and innocent civilians, and all he was concerned about was ‘violence in Karachi’?

‘Sir, shouldn’t you be more concerned about Lahore?’ I asked, smiling.

He failed to get my drift: ‘Paracha sahib, why don’t you people do something about the MQM?’

By now my smile had turned into a polite laughter: ‘Sir, was it the MQM or the PPP that blew up the Sufi shrine in Lahore the other day?’

‘I know you’re not so naïve, Paracha sahib,’ he said, ‘you know who is behind all these terrorist attacks…’

‘Of course, I do,’ I replied. ‘These terrorists are the same monsters whom we have been nurturing in the name of jihad all these years and …’

He let out a loud burst of laughter: ‘What sort of a media man are you, Paracha sahib. These so-called terrorists are all enemy agents!’

I knew that was coming, right on cue.

‘Well said!’ I applauded. ‘Whenever there is violence in Lahore it is blamed on anti-Islam agents, but violence in Karachi is blamed on the MQM, the PPP and the ANP? Very convenient.’

Switching back to Punjabi, the gentleman gave me a sideways grin: ‘Paracha sahib, you are a Punjabi, so I wonder why the sympathy with the MQM? Is it fear?’

I then reverted back to speaking in Punjabi: ‘Sir jee, it is not fear. It is curiosity about the mindset of the people of Punjab. We are highly intrigued about how in the face of overwhelming evidence that it is our own people who in the name of Islam, are going about blowing up mosques, shrines and markets in the Punjab, but you continue living in a make-believe world of conspiracies. But what do we, Karachiites know. We are, after all gangsters, right?’ I smiled.

A strain of slight anger suddenly cut across the gentleman’s face: ‘We are more concerned about the corruption and the scoundrels in this government.’

‘Very noble of you, sir,’ I replied.

‘Give Nawaz Sharif 5 years and he will change the fate of this country!’ he announced.

‘But sir, Mian Sahib so far only gets votes from the Punjab. And anyway, isn’t a cousin of yours a member of the PML-Q?’ I asked.

He ignored the PML-Q remark: ‘Mian sahib will sweep the next elections …’

‘…in the Punjab,’ I interrupted. ‘Is Pakistan only about the Punjab then?’

He laughed and shook his head: ‘That’s the problem with you. Punjab is blamed for everything! What sort of a Punjabi are you?’

‘Wah, Sir jee,’ I said with a smile, ‘it is fine if you go on and on about the Mohajirs, Sindhis, the Pashtuns and the Baloch, but throw up your arms in shock when someone even mentions the Punjab?’

‘We have done so much for Pakistan!’ He announced proudly.

‘Were you the only ones?’ I asked.

‘Why do you think Pakistan’s enemies are targeting the Punjab? They know its’ importance.’ He said.

‘Oh, so do we,’ I replied. ‘But we, Pakistanis, are our own enemies. Those killing their own countrymen in the name of faith, politics, greed or ideology anywhere in Pakistan, are the enemy.’

‘Faith has nothing to do with this!’ He announced, now with a sterner expression.

‘Precisely!’ I said, ‘and yet we keep calling it faith!’

By now he had lost me: ‘What do you mean?’

‘Sir, Karachiites or as you would like to call us – gangsters – believe that the Punjab does not condemn extremists enough. It is as if by doing this they feel they would be condemning faith itself, is that true?’ I asked.

‘We don’t think these extremists are even Muslim!’ He shot back.

‘Well, they say they are the best Muslims out there,’ I replied. ‘And anyway, if you think they are not Muslim, then why not condemn them the way they should be?’

‘How come you guys don’t condemn the MQM or the PPP?’ he snapped back.

‘Oh, we do,’ I retorted. ‘Just the way political parties should be criticised. But then they have yet to blow up mosques, shrines and markets, if you know what I mean.’ I replied.

‘And the PML-N does?’ He asked, raising his voice a notch.

‘Absolutely not!’ I said. ‘It just doesn’t condemn extremists the way it should, that’s all. Is it fear?’

The argument ended when his cell phone rang and he excused himself.

I said goodbye and on my way out was met by his manager who gave some going-away gifts: beautiful unstitched fabric, a nice shirt and a cardboard box.

Curious about what was in it, I opened the box in the car and found 9 slim booklets – all of them were on how to become a better Muslim. Viola!

It seems that the industrialists are getting spiritually industrious as well.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM

The map man

Nadeem F. PARACHA

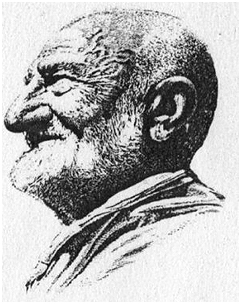

Rehmat Ali, Provided by the writer

Standard text books in Pakistani schools all describe Chaudhry Rehmat Ali as the man who coined the word Pakistan. He is also defined as being one of the main architects of the idea of a separate Muslim homeland in South Asia — an idea that was echoed some years later by poet and philosopher, Mohammad Iqbal, and eventually shaped into reality by Mohammad Ali Jinnah in August 1947.

Not much else is mentioned in these text books about Rehmat Ali. He is presented as a one-shot wonder, someone who came up with the name and idea of Pakistan but then just simply vanishes from the pages after 1940!

Late last year while going through some piles of books at a second-hand bookstore in Karachi’s Boat Basin area, I came upon a grubby thin publication called Pakistan: The Fatherland of Pak Nation.

This book that I ended up buying (for just Rs100) was a 1956 reprint of a 1934 pamphlet authored by Rehmat Ali. It’s a fascinating read! More so because it can actually help one understand the intellectual (and maybe even psychological) disposition of a vital character in the history of the making of Pakistan, but someone who never managed to get more than a paragraph or two in most text books.

How Rehmat Ali literally mapped the creation of a separate Muslim state

After reading the book one can also understand why this happened. The book reproduces a 1934 pamphlet that Rehmat Ali wrote when he was a student in England.

In it he outlines a theory that suggests that Muslims of the region should be working towards carving out their own sovereign homeland not only because a Hindu-majority India was detrimental to the political, cultural and economic interests of the Muslims, but also because such a homeland already existed across various periods of history.

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, many religious parties picked up Rehmat Ali’s idea and began to claim that the seeds of Pakistan’s creation were first sowed by the invading forces of Arab commander, Mohammad Bin Qasim (in the early 8th century), but Rehmat Ali’s imagined history actually went back even further.

To him the separate homeland in the region that he was talking about first emerged in a time period he calls ‘The Dawn of History.’ Though he doesn’t attach any date or year to this, but with the help of a map (titled ‘Pakistan at the Dawn of History’), he explains how the civilisations that first emerged beside the mighty Indus and those that sprang up around the banks of River Ganges were somewhat separate.

But to Rehmat the ‘dawn’ fully appears in the 8th century when the Arab Umayyad Empire extended its reach into Sindh, situated on either sides of the mighty Indus. This he also explains with the help of a map. The Sindh part on the map is labelled as ‘Pakistan.’

Thus follow 13 more maps covering various periods from the eighth to early 20th centuries. The area that Rehmat Ali calls Pakistan expands and shrinks, enlarges and then contracts again across the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal era, and the early British period, and all the way till 1942.

The last of these maps is titled ‘The Pak Millat 1942’. The Pak Millat constitutes all of what is Pakistan and Bangladesh today; and pieces of Muslim-majority areas in central and north India which Ali describe as being ‘Usmanistan’, ‘Farooqistan’, ‘Siddiqistan’ and Haideristan.’

Rehmat Ali’s style of writing is almost frantic, impulsive and that of an alarmist, warning the Muslims of India that a Pakistan or ‘Pak Millat’ that he was purposing is already out there and needed to be reclaimed.

So in a way, instead of actually propagating a new Muslim homeland, Rehmat Ali was really asking the Muslims to reclaim (and declare) geographical areas that had always been their home.

When Rehmat Ali first published his pamphlet (and 13 maps), he was largely ignored by a bulk of Muslim political leaders and intellectuals in India. Some even saw him as being an overexcited youth lost in the mad haze of political fantasies, if not a downright crank!

Alyssa Ayres in her book Language and Nationalism in Pakistan quotes Jinnah, describing the pamphlet as ‘ravings of a student …’

One should be reminded that till Iqbal decided to (albeit tentatively) use Rehmat Ali’s word ‘Pakistan’ in 1940, Jinnah was still very much interested in maintaining a united India.

In fact, according to author and scholar Ayesha Jalal, Jinnah was still trying to work towards reaching a workable post-colonial relationship between the Muslims and the Hindus of region till the early 1940s!

Though the word that Rehmat Ali had coined (‘Pakistan’) eventually managed to stir the imagination of millions of Muslims and their leaders, its inventor was soon at loggerheads with most of these leaders.

According to famous historian, K.K. Aziz, Jinnah saw the name as a throwaway anomaly, and an impulsive invention of certain students (i.e. Rehmat Ali).

In a 1943 speech, Jinnah told a crowd in Delhi that before 1940 the word Pakistan had been used more by the Hindu and British press than by the Muslims; and that it was actually imposed upon the Muslims of India by these two communities.

However, in the same speech, Jinnah announced that he will embrace the word because now it had become synonymous with Muslim struggle in India.

Rehmat Ali had actually met Jinnah in 1934, only days after he had authored his pamphlet. According to K.K. Aziz, Jinnah, after noticing the restless and impulsive nature of the young ideologue, told him ‘My dear boy, don’t be in a hurry; let the waters flow and they will find their own level …’

Jinnah’s level-headed and unruffled disposition ran against Rehmat Ali’s impulsive and volatile personality. He remained in England during most of what became known as the ‘Pakistan Movement;’ and even after the creation of a Pakistan that he had first theorised in his explosive pamphlet in 1934, Rehmat Ali arrived in the new country almost a year after its formation.

He vehemently criticised Jinnah and his party (the Muslim League) for compromising the ‘full idea of Pakistan’ and getting only a portion of what he had envisioned (in his pamphlet).

Though Jinnah too wasn’t satisfied with what he got (as Pakistan), he (and the League) had decided to make the best of whatever they had managed to win.

Rehmat Ali continued to deliver his scathing criticism. But soon after Jinnah’s unfortunate death in 1948, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan (a close confidant of Jinnah), lambasted Ali and ordered him to leave the country.

Rehmat returned to England. Three years later he was found dead in his bedroom. He had passed away in his sleep. His body was found a few days after his demise. He was 55.

As Alyssa Ayres puts it in her book, Rehmat ended up becoming nothing more than a footnote in the history of Pakistan — a country that he had theorised had existed since the ‘dawn of history.’

Curtsey:Dawn, Sunday Magazine, June 21st, 2015

My name is Pakistan and I’m not an Arab

NADEEM F. PARACHA

In 1973, my paternal grandparents visited Makkah to perform the first of their two Hajj pilgrimages.

With them were two of my grandmother’s sisters and their respective husbands.

Upon reaching Jeddah, they hailed a taxi from the airport and headed for their designated hotel.

The driver of the taxi was a Sudanese man. As my grandparents and one of my grandmother’s sisters settled themselves in the taxi, the driver leisurely began driving towards the hotel and on the way inserted a cassette of Arabic songs into the car’s Japanese cassette-player.

My grandfather who was seated in the front seat beside the driver noticed that the man kept glancing at the rear view mirror, and every time he did that, one of his eyebrows would rise.

Curious, my grandfather turned his head to see exactly what was it about the women seated in the back seat that the taxi driver found so amusing.

This was what he discovered: As my grandmother was trying to take a quick nap, her sister too had her eyes closed, but her head was gently swinging from left to right to the beat of the music and she kept whispering (as if in quiet spiritual ecstasy) the Arabic expression Subhanallah, subhanallah …’

My grandfather knew enough Arabic to realise that the song to which my grandmother’s sister was swinging and praising the Almighty for was about an (Egyptian) Romeo who was lamenting his past as a heart-breaking flirt.

After giving a sideways glance to the driver to make sure he didn’t understand Punjabi, my grandfather politely asked my grandmother’s sister: ‘I didn’t know you were so much into music.’

‘Allah be praised, brother,’ she replied. ‘Isn’t it wonderful?’

The chatter woke my grandmother up: ‘What is so wonderful?’ She asked. ‘This,’ said her sister, pointing at one of the stereo speakers behind her. ‘So peaceful and spiritual …’

My grandfather let off a sudden burst of an albeit shy and muffled laughter. ‘Sister,’ he said, ‘the singer is not singing holy verses. He is singing about his romantic past.’

My grandmother started to laugh as well. Her sister’s spiritual smile was at once replaced by an utterly confused look: ‘What …?’

‘Sister,’ my grandfather explained, ‘Arabs don’t go around chanting spiritual and holy verses. Do you think they quote a verse from the holy book when, for example, they go to a fruit shop to buy fruit or want toothpaste?’

I’m sure my grandmother’s sister got the point. Not everything Arabic is holy.

Even though I was only a small child then I clearly remember my grandfather relating the episode with great relish. Though he was an extremely conservative and religious man and twice performed the Hajj, he refused to sport a beard, and wasn’t much of a fan of the Arabs (especially the monarchical kind).

He was proud of the fact that he was born in a small town in north Punjab that before 1947 was part of India.

In the early 1980s when Saudi money and influence truly began to take hold on the culture and politics of Pakistan, there were many families (especially from the Punjab) that actually began to rewrite their histories.

For example, families and clans that had emerged from within the South Asian region began to claim that their ancestors actually came from Arabia.

Something like this happened within the Paracha clan as well. In 1982 a book (authored by one of my grandfather’s many cousins) claimed that the Paracha clan originally appeared in Yemen and was converted to Islam during the time of the Holy Prophet (Pbuh).

The truth, however, was that like a majority of Pakistanis, Parachas too were once either Hindus or Buddhists who were converted to Islam by Sufi saints between the 11th and 15th centuries.

When the cousin gifted his book to my grandfather, he rubbished the claim and told him that he might attract Saudi Riyals with the book but zero historical credibility.

But historical accuracy and credibility does not pan well in an insecure country like Pakistan whose state and people, even after six decades of existence, are yet to clearly define exactly what constitutes their nationalistic and cultural identity.

After the complete fall of the Mughal Empire in the 19th century till about the late 1960s, Pakistanis (post-1947), attempted to separate themselves from other religious communities of the region by identifying with those Persian cultural aspects that had reigned supreme in Muslim royal courts in India, especially during the Mughal era.

However, after the 1971 East Pakistan debacle, the state with the help of conservative historians and ulema made a conscious effort to divorce Pakistan’s history from its Hindu and Persian past and enact a project to bond this history with a largely mythical and superficial link with Arabia.

The project began to evolve at a much more rapid pace from the 1980s onwards. The streaming in of the ‘Petro Dollars’ from oil-rich monarchies and the Pakistanis’ increasing interaction with their Arab employers in these countries, turned Pakistan’s historical identity on its head.

In other words, instead of investing intellectual resources to develop a nationalism that was grounded and rooted in the more historically accurate sociology and politics of the Muslims of the region, a reactive attempt was made to dislodge one form of ‘cultural imperialism’ and import by adopting another.

For example, attempts were made to dislodge ‘Hindu and Western cultural influences’ in the Pakistani society by adopting Arabic cultural hegemony that came as a pre-requisite and condition with the Arabian Petro Dollar.

The point is, instead of assimilating the finer points of the diverse religious and ethnic cultures that our history is made of and synthesise them to form a more convincing and grounded nationalism and cultural identity, we have decided to reject our diverse and pluralistic past and instead adopt cultural dimensions of a people who, ironically, still consider non-Arabs like Pakistanis as second-class Muslims.

CURTSEY:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED JUL 28, 2013

Exit God, enter madness

NADEEM F. PARACHA

On Wednesday, 4th of July, a frenzied mob broke into a police station in Bahawalpur (South Punjab). The mob’s target was a ‘malang’ (vagabond), the sort that have been found in and around numerous shrines of Sufi saints in the sub-continent for centuries.

The malang, whom many people of the area also described to be a man not very sound of mind, had been taken into custody by the area’s police after some people accused him of desecrating the sanctity of the Muslim holy book, the Quran.

So on Wednesday as the malang sat behind bars at a police lock-up and as most of the cops kept giving him sideways glances, cracking vague, pitying grins at the malang’s state of mind and habit of talking to himself, the mob surrounded the police station, demanding that the ‘blasphemer’ be handed over.

The cops refused, pleading that the case against the man shall be decided by the courts. As if already surprised that their fellow Muslims in uniforms hadn’t lynched the ‘blasphemer’ themselves, the mob thrust forward in an attempt to break into the police station.

A few cops rushed out with batons and teargas canisters trying to push the mob back that by now had grown to over a hundred enraged men with an audience of another hundred or so onlookers who, as usual, hang around such situations like silent, inanimate zombies.

As one of the cops frantically pleaded for reinforcements from his superiors on the phone, the mob had already barged into the lock-up. They went straight for the room in which the malang was being held.

Newspapers reported that the room/jail was being guarded by two armed policemen. A reporter of an Urdu daily told me that the cops did raise and point their guns at the approaching mob and wanted to fire, but seeing they were heavily outnumbered they decided to simply block the way.

Of course, how could they have? They were not only brushed away but mercilessly beaten, as the mob finally broke into the room, got hold of the terrified malang, dragged him outside and began to beat him with fists, kicks, iron rods and sticks.

Some witnesses (the mesmerised zombies) told reporters that they could hear the malang screaming and pleading the mob for mercy. But the onlookers stood still and so did the bruised cops, praying that the promised reinforcements would arrive before the mob slaughtered the malang and send him to hell for insulting Islam – the ‘religion of peace.’

The reinforcements did arrive. But by then the mob had had its fill of vengeance and blood. It had battered a vagabond and a mentally disturbed person to death. And as if that wasn’t enough to quench its blood thirst, it set the limp, bloodied body of the man on fire!

Deluded as we have become about our religious and national identities and priorities, I’m sure after seeing flames rise from the evil blasphemer’s dead body, many pious men in the mob must have looked at the sky, trying to penetrate their blood-shot gaze into the seventh sky where God resides, expecting the Almighty to begin showering rose petals on them.

That didn’t happen, and no one was willing to suggest that in all probability God had actually been repulsed by the act.

Yet again, the nation heard and saw its faith and holy texts being ‘avenged’ not by God-fearing men, but by a mob of retarded, subhuman filth.

Almost all leading media outlets in the country carried the horrific story. And so did the western media that continues to scratch its head trying to figure out just how inflammable and helplessly retarded Pakistan’s state institutions, judiciary, politics and society have become.

The self-claimed ‘bastion of Islam’ has gradually mutated into becoming a bastion of deluded messiahs and mindless, violent ranting machines to whom anything, from incoherent malangs to the reopening of Nato supply routes, are conspiracies against Islam.

Even more than 24 hours after the gruesome incident, no-one seems to even know the murdered man’s name.

Who was he? Did he really desecrate the Quran? Or was he too a victim of the many reasons that usually drive conniving men to whip up hatred among impressionable, frustrated people to settle personal and economic scores against enemies by accusing him/her of blasphemy?

Or was the incident part of the 200-year-old battle between the Sunni Barelvi and Sunni Deobandi groups in the subcontinent in which both the sides have denounced each another as heretical?

Ever since the reactionary Ziaul Haq dictatorship began to give shape to laws that would eventually become to be known as the ‘Blasphemy Laws,’ it is believed more than 60 per cent of cases concerning one party accusing the other of blasphemy involve Barelivis and Deobandis pointing fingers at each other.

Various governments that took over after Zia’s demise in 1988, especially those belonging to the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the one run by General Pervez Musharraf, have made several attempts to repeal the laws that various moderate and liberal Islamic scholars have insisted has no precedence in the history of Islamic jurisprudence.

Javed Ahmed Ghamdi is one of the few well-known Islamic scholars in Pakistan who has publicly insisted that the country’s Blasphemy Laws have no precedence in the history of Islamic jurisprudence, and are entirely man-made (as opposed to being divinely ordained). In 2009, Ghamdi began receiving threats from the country’s various sectarian and Islamist organisations. He had to quietly go into hiding for which he flew out to Malaysia.

For example, during both the Benazir Bhutto governments (1988-91/1993-96), she hinted her desire to at least amend the controversial laws but her attempt was thwarted by religious parties even before she could put up the issue for debate in the parliament.

In the mid-2000s, the Musharraf dictatorship also tried its hand to repel the laws, only managing to push through soft, superficial changes.

In 2010, PPP legislator and current Pakistan ambassador to the US, Sherry Rahman, prepared a bill for the parliament that pleaded changes in the law, but nothing came from it – especially after veteran PPP man and governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer, was assassinated by a crazed bodyguard who believed Taseer had committed blasphemy.

Taseer had sympathised with a poor Christian woman who was arrested after being accused (by those trying to convert her to Islam) for blasphemy.

Salman-Taseer

Former Governor of Punjab and veteran leader of the PPP, Salman Taseer, who was gunned down by a crazed fanatic who accused him of committing blasphemy.

Religious outfits such as the fundamentalist Jamat-i-Islami (JI), the Deobandi Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI) and the Barelvi Sunni Ittihad Council (SIC) have all been at the forefront of resisting any move made by non-religious parties to repeal or even amend the Blasphemy laws.

However, in the last decade or so, a number of sectarian and jihadist organisations along with some prominent media men too have jumped into the fray.

The year Taseer was murdered and there was talk of Sherry Rehman wanting to introduce her bill in the parliament, JI, JUI and SIC held a number of rallies across the country against the move.

Also present at the rallies were leaders from banned sectarian and militant organisations.

What’s more, well-known TV anchors like Aamir Liaqat and investigative reporter and ‘analyst’ Ansar Abbasi and some others in the media have been openly using air time and column space to not only blunt any move to even amend the controversial law, but to also (and actually) blame the victims of the law and mob action partaken in the name of Islam.

Another section of the civil society, the lawyers, still reeling from the euphoria of 2006-7’s ‘Lawyers Movement’ against the Musharraf regime, can now be seen stretching the residue of the movement into the religious domain.

A number of lawyers in various urban centres of the Punjab were caught on camera showering rose petals on Taseer’s murderer. Then, only recently, the Lahore Bar Council actually banned Shezan food products on its premises because ‘Shezan was owned and run by Ahamdis.’

Ansar Abbasi getting angry at a newscaster for repeatedly showing images of a woman being flogged by religious extremists in Swat in 2009. He first tries to suggest that the flogging might have been according to the ‘dictates of Sharia.’ Then he says he disagrees with those who are calling the act barbaric.

Apart from the fact that the controversial law has witnessed numerous cases in which men have tried to get rid of enemies for economic, sectarian and entirely non-religious reasons by misusing the law against them, another fall-out has been how this law has ended up actually encouraging people to take vigilante action.

When the mentally disturbed malang was murdered by the Bhawalpur mob, this was not the first time that such brutality had taken place in the name of protecting faith in Pakistan.

Interestingly, most cases involving mobs attacking those accused of blasphemy have taken place in central and southern Punjab. Over the past two decades Punjab as a whole has been going through a religious metamorphosis of sorts that is seeing a rise in not only overt religiosity and exhibitionism in the province, but a more rapid mushrooming of jihadi and sectarian outfits.

Civilian political and state institutions seem almost helpless to stem the tide, fearing retaliation and accusations of siding with the ‘blasphemers.’

Apart from the way Taseer was murdered and how Sherry Rehman and late Fauzia Wahab were threatened, the federal government (under a PPP-led coalition) and the one in the Punjab (run by the PML-N), seem clueless on how to keep the proliferation of hate literature and hate sermons in seminaries and mosques in check and under watch.

In fact, non-religious but right-wing parties like the PML-N and Imran Khan’s PTI haven’t shied away from cultivating links with certain sectarian outfits and personalities, some of whom have actually hailed vigilante action against ‘heretics’ and ‘blasphemers’.

militant-flags-at-PTI-dharna-karachi

PTI chief Imran Khan, giving a speech at a PTI rally. Seen in the crowd are flags of the Jamat-i-Islami and the banned sectarian organisation, Sipah Sahaba Pakistan (SSP).

SSP

Punjab law Minister and PML-N leader, Rana Sannaullah, seen on stage with the leader of the banned SSP.

Image: Pakistani lawyers chant slogans in suppo

Lawyers in Lahore cheer for the killer of Salman Taseer outside a court. They had showered him with rose petals and hailed him as a hero. Many of them had also been part of the ‘Lawyers Movement’ against the Musharraf regime.

Aamir Liaqaat

Famous TV religious anchor, Aamir Liaqat, was accused by the Ahamadi community for instigating violence against Ahmadis through his show. Four Ahmadis were murdered in Lahore in 2007 and the community accused Liaqat’s show. Though no legal action was taken, Liaqat, who was then a member of the MQM, was fired from the party. He was soon shown the door by the TV channel as well. However, this year the same channel decided to get him back and he is set to revive his show from this year’s Ramazan.

So who was the malang? What was his name? What did he do? The following is what I could gather from some reporters who were trying to decipher the same.

His name is still unknown, most probably because he came from a poor economic background. According to some reporters, he was well known by at least some of those who decided to kill and then set him on fire.

Many people of the area knew him as a vagabond who was not quite sane. It is still not known exactly who thought that this ragged looking and mentally disturbed man desecrated the holy book.

But one reporter told me that some people of the area were of the view that the malang was an ‘ashiq’ of Mansur Al-Hallaj – the famous 10th century Sufi saint, scholar and poet who was put to death by the authorities in Iraq for committing blasphemy.

Hallaj

A painting showing the hanging of Sufi saint and poet Mansur Al-Hallaj. He was hanged by Abbasid caliph, Al-Muqtadir in 922 CE, after the orthodox ulema and molvis at Muqtadir’s court accused Hallaj of committing blasphemy. In a fit of Sufi devotional rite, Al-Hallaj is reported to have shouted ‘An? l-?aqq’ (I am the truth). The ulema took the statement to mean that Hallaj was declaring he was God. Sufis, however, believe that Al-Hajjaj had simply reached the pinnacle of devotional consciousness and that Muqadir and his ulema got him executed because his unorthodox ways of teaching Islam had become popular with the masses and thus a threat to the Caliphate.

Details about the poor malang are at best sketchy and based on speculations, apart from the fact that he was mentally unsound.

It is also likely that even if this man actually had a family somewhere, it would hesitate to come forward.

Families of those arrested for blasphemy or killed usually become targets of harassment. The ordeal becomes like a nightmare that one fails to wake up from – until the defenders of the faith provide another hell-bound victim so the cycle begins again and the enthusiasm to kill and burn enemies of God remains as animated and constant as ever.

As one distraught friend of mine once prayed: ‘May Allah save Islam from Pakistan.’

Curtsey: DAWN.COM PUBLISHED JUL 05, 2012

The enigmatic Pakhtun

NADEEM F. PARACHA

Recently a Pakhtun friend of mine who is doing his doctorate in Anthropology from a European university emailed me the following: “Nothing has damaged us Pakhtuns more than certain myths about our character that were not constructed by us”.

We were exchanging views on how some self-proclaimed experts on Pakhtun history and character in Pakistan were actually using the stereotypical aspects of this character to deter the Pakistani state from undertaking an all-out military operation against religious extremists in the Pakhtun-dominated tribal areas of the country.

My friend (who originally hails from the Upper Dir District in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) also made another interesting observation: “You know, these myths have been engrained so deep into the psyche of today’s Pakhtuns that if one starts to deconstruct them, he or she would first and foremost be admonished by today’s young Pakhtuns. They want to believe in these myths not knowing that, more often than not, these myths have reduced them to being conceived as some kind of brainless sub-humans who pick up a gun at the drop of a hat to defend things like honour, faith, tradition, etc.”

But in his emails he was particularly angry at certain leading non-Pakhtun political leaders, clerics and even a few intellectuals who he thought were whipping up stereotypical perceptions and myths about the Pakhtuns to rationalise the violence of extremist outfits like the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) that has a large Pakhtun membership.

He added that in the West as well, many of his European and American contemporaries in the academic world uncritically lap-up these perceptions and myths. He wrote: “They are surprised when they meet Pakhtun students here (in Europe), who are intelligent, rational, and humane and absolutely nothing like Genghis Khan”!

There have been a number of research papers and books written on the subject that convincingly debunk the myths attached to the social and cultural character of the Pakhtuns.

Almost all of them point an accusing finger at British Colonialists for being the pioneers of stereotyping the Pakhtuns.

Adil Khan in Pakhtun Ethnic Nationalism: From Separation to Integration writes that in 1849 when the British captured the southern part of Afghanistan, they faced stiff resistance from the Pakhtun tribes there. The British saw the tribes as the anti-thesis of what the British represented: civilisation and progress.

This is when the British started to explain the Pakhtuns as ‘noble savages’ — even though in the next few decades (especially during and after the 1857 Mutiny), the colonialists would face even more determined resistance from various non-Pakhtun Muslims and non-Muslims of the region.

From then onwards, British writers began to spin yarns of a romanticised and revivalist image of the Pakhtuns that also became popular among various South Asian historians.

Adil Khan complains that such an attempt to pigeonhole the Pakhtuns has obscured the economic and geographical conditions that have shaped the Pakhtun psyche. What’s more, the image of the unbeatable noble savage has been propagated in such a manner that many Pakhtuns now find it obligatory to live up and exhibit this image.

The myths associated with the Pakhtuns’ character have most recently been used to inform the narratives weaved by those who see religious militancy emerging from the Pakhtun-dominated areas in the north-west of Pakistan as a consequence of the state’s careless handling of the traditions of the ‘proud Pakhtun tribes’ (which may have triggered the ‘historical’ penchant of these tribes to inflict acts of revenge). Interestingly, the same myths were once also used by secular Pakhtun nationalists.

One of the most popular architects of Pakhtun nationalism, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, banked on the myth of Pakhtuns being unbeatable warriors to construct the anti-colonial aspect of his Pakhtun nationalist organisation, the Khudai Khidmatgar.

Earnest Gellner in Myths of Nation & Class in Mapping the Nation is of the view that though the Pakhtuns are an independent-minded people and take pride in many of their centuries-old traditions, they are largely an opportunistic and pragmatic people.

When Pakistan became an active participant in the United States’ proxy war against the Soviet forces that had entered Afghanistan, the Ziaul Haq dictatorship — to whip up support for the Afghan mujahideen — used state media and anti-Soviet intelligentsia to proliferate the idea that historically the Pakhtuns were an unbeatable race that had defeated all forces that had attempted to conquer them.

One still hears this, especially from those opposing the Pakistan state’s military action in the country’s tribal areas. But is there any historical accuracy in this proud proclamation?

Not quite. The truth is that the Pakhtuns have been beaten on a number of occasions. Alexander, Timur, Nadir Shah, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and the British, were all able to defeat the Pakhtuns.

In the 2008 paper, Losing the Psy-war in Afghanistan, the author writes: ‘True, the British suffered the occasional setback but they eventually managed to subdue the Pakhtun tribes. Had the British wanted they would have also continued to rule Afghanistan, only they didn’t find it worth their while and preferred to let it remain a buffer between India and Russia. The Russians (in the 1980s) too would never have been defeated had the Soviet economy not collapsed — and it didn’t collapse because of the war in Afghanistan — and had the Americans not pumped in weapons and money to back the so-called Mujahideen.’

The paper adds: ‘… while Pakhtuns are terrific warriors for whom warfare is a way of life, they have always succumbed to superior force and superior tactics. The Pakhtuns have never been known to stand against a well-disciplined, well-equipped, motivated, and equally ruthless force.’

Curtsey: DAWN.COM-MAR 02, 2014

When the mountains were red

Nadeem F. Paracha

Bacha Khan (1890-1988): The father of modern Pushtun nationalism

Many Pakistani Pushtuns find themselves in a spot of bother when some political commentators and analysts define extremist organisations like the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) as an extension and expression of Pushtun nationalism.

Though religion has always played a central role in the make-up of Pushtun identity, Pushtun nationalism (especially in the 20th century) was always a more secular and left-leaning phenomenon. It still is.

This nationalism’s modern manifestation was founded on the thoughts and actions of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan) and expressed through such left-wing parties as National Awami Party (NAP), Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party (PkMAP) and the Awami National Party (ANP).

However, for nearly three decades now, or ever since the beginning of the US/Pakistan/Saudi-backed ‘jihad’ against the Soviet forces in Afghanistan in the 1980s, Pushtun identity (at least in popular imagination) has been gradually mutating into becoming to mean something that is akin to being aggressive, fanatical and entirely religious.

Yet, till 2008 the county’s Pushtuns were enthusiastically voting for secular Pushtun nationalist parties like the ANP, and till even this day, there are a number of Pushtuns who are openly canvasing to eradicate not only religious violence and extremism from the Pushtun-dominated province of Khyber-Puskhtunkhwa (KPK), but also busy working towards debunking the belief that Pushtuns are by nature fanatical, driven by revenge and radically ‘Islamist’ in orientation.

Such Pushtuns point out the unique Pushtun-centric secularism of men like Bacha Khan and how left-wing parties like NAP were once KPK’s most popular exponents of electoral politics.

They blame the Pakistani ‘establishment’ for corrupting the notion of Pushtun nationalism by radicalising large portions of the Pushtuns through radical religious indoctrination and the Saudi ‘Petro Dollar.’

The idea was to neutralise Pushtun nationalism that had been the leading player in NAP, a party that also included Baloch and Sindhi nationalists, and was suspiciously eyed (by the establishment) to have had separatist and anti-Pakistan sentiments.

In the last decade or so – especially ever since extremist violence gripped the country, and with the KPK and the tribal areas that surround the province becoming the epicentre of this violence – various Pushtun parties, groups and individuals have been aggressively using political, social and cultural platforms to challenge the perception that religious extremism found in certain Pushtun-dominated militant outfits have anything to do with Pushtun culture or nationalism.

But so far it has been an uphill task and unfortunately the word Pushtun continues to trigger images of bushy, violent fanatics exploding themselves up in markets and mosques or beheading ‘infidels’ in the hills and mountains of KPK and the tribal areas.

But how many know that most of the hilly, rugged areas that have been held and have become bases of extremist outfits in KPK and its surrounding areas, were once bastions of militant Maoist groups?

This slab of history has been forgotten in the noise emitting from those who only have a superficial understanding of Pushtun nationalism and continue to equate it with religious fundamentalism.

Post-1947 Pushtun nationalism empathised with Sindhi, Baloch and Bengali nationalisms (and vice versa), all of whom exhibited concern that the Pakistani state’s centralising tendencies and emphasis on adopting a single variant of Islam, language and culture were cosmetic and artificial constructs to undermine and eliminate thousands of years of the history and dynamics of Pushtun, Sindhi, Baloch and Bengali cultures.

These nationalists saw state policies to be an extension of Punjab’s economic and political hegemony. They eventually came together to form the National Awami Party (NAP).

Formed in 1957, NAP included pioneering Pushtun, Baloch, Sindhi and Bengali thinkers and politicians.

NAP’s founding members included: Former Muslim Leaguer and socialist, Mian Ifikharuddin; Sindhi scholar and nationalist, GM Syed; Pushtun nationalist and thinker, Bacha Khan; Pushtun nationalist, Abdul Samad Achakzai; Bengali leftist leader, Maulana Bhashani; and Baloch nationalist, Ghaus Baksh Bezinjo.

A number of intellectuals also joined the party, including popular Urdu poet and activist, Habib Jalib.

It described itself to be a socialist-democratic party working towards achieving democratic reforms and greater autonomy for the country’s non-Punjabi and non-Mohajir populations and provinces – even though NAP also included Mohajir and Punjabi activists who were once associated with the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) that was banned in 1954.

NAP was thus radically opposed to the ‘One Unit’ – a state-backed initiative that had clumped together all of West Pakistan as one province (most probably to equal and neutralise the Bengali majority in East Pakistan).

When the 1956 Constitution promised to hold Pakistan’s first ever direct election based on adult franchise by 1958, the NAP was poised to bag the most seats in West Pakistan as well as in the Bengali-dominated East Pakistan.

The other two major parties of the era, the Muslim League and the Republican Party, were both besieged by infighting, whereas religious parties like the Jamat-i-Islami (JI) and Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI) did not have much electoral support. NAP stood out to be the most organised outfit at the time.

However, the promised elections never took place. Field Martial Ayub Khan imposed Martial Law through a military coup in 1959 and banned all political parties.

NAP leaders were released from jail when Ayub lifted the ban on political parties and authored a new constitution in 1962.

NAP returned to agitate and demand for provincial autonomy, removal of the One Unit, the holding of direct election, and the adoption of a non-allied policy in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

However, by the time of the 1965 Presidential election, some cracks began to appear in the party.

Due to the growing hostility between the time’s two communist powers, Soviet Union and China, various leftist parties of the world began experiencing splits.

But NAP, in spite of the fact that a pro-China (Maoist) and a pro-Soviet faction had emerged in it as well, remained intact.

Nevertheless, when the pro-US Ayub regime’s foreign policy began to tilt a bit towards communist China, NAP leader, Maulana Bhashani, a pro-China figurehead, insisted that NAP begin to support Ayub.

So though on the surface NAP remained to be a united front, beneath the veneer its leaders had begun to disagree among themselves on the question of supporting Ayub.

When Ayub set out to compete with Fatima Jinnah in the 1965 Presidential election, the Bhasahni faction of NAP supported him whereas the Wali Khan faction opposed him and backed Jinnah instead.

In 1966, when the 1965 Pakistan-India war ended in a stalemate, Ayub’s young Foreign Minister, Z A. Bhutto (the initial architect of Pak-China relations), resigned, accusing Ayub of ‘losing the war on the negotiating table.’

Bhutto’s animated antics in this respect were hailed by leftist student groups and eventually he gallivanted towards finding a position for himself in NAP.

But since NAP was packed with veteran leftist and nationalist figureheads, Bhutto decided to form his own socialist party, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).

Though a Sindhi, his party (formed in 1967) attracted the interest of various socialist and Marxist ideologues from the Punjabi and the Urdu-speaking communities. Many of them had been with NAP but were alienated by the party’s aggressive anti-Punjab stance.

In 1967 the split in NAP became an open secret. During its on-going analysis on how to achieve a socialist revolution in Pakistan, the NAP leadership failed to come to a common consensus.

The pro-Soviet faction (led by Bacha Khan’s son, Wali Khan), suggested working to put Pakistan on a democratic path and then achieve the party’s goals of provincial autonomy and socialist policies by taking part in an election.

The pro-China faction led by Bhashani disagreed and advised supporting Pakistan’s growing relationship with China. The faction also rejected democracy and labelled it as being a tool of the bourgeoisie. Bhashani instead advocated that the party should ally and work with peasant groups to initiate revolutionary land reforms.

The pro-Soviet NAP became NAP-Wali while the pro-China one became NAP-Bhashani.

The largest student party at the time, the left-wing National Students Federation (NSF) that had become the student-wing of NAP too suffered a split with the majority of NSF groups taking the Maoist line.

Most of these however began to associate themselves more with the politics of the PPP, whereas two new student groups, Pushtun Students Federation (PkSF), and Baloch Students Organisation (BSO), came under the umbrella of NAP-Wali.

It was NAP-Wali that became the bigger faction, mainly due to the fact that the party’s main Pushtun, Baloch and Sindhi leadership (sans GM Syed) decided to join the Wali faction.

Also, whereas the pro-Soviet student and trade unions also attached themselves to the Wali faction, most Maoist groups, instead of backing the Bhashani faction, decided to attach themselves with Bhutto’s PPP.

But soon a third faction in NAP appeared. A more radical group within NAP-Wali broke away in 1968 and decided to adopt the Maoist strategy of achieving a socialist revolution through an armed struggle and organising peasant militias.

Thus was born the Mazdoor Kissan Party (Worker & Peasants Party) that held its first convention in Peshawar in 1968.

Populist leftist politics reached a nadir in Pakistan in the late 1960s. Leftist student groups like the NSF and the National Students Organization (NSO) controlled most of the country’s student unions, and along with labour unions, PPP and NAP-Wali successfully agitated against the Ayub dictatorship and forced him to step down.

The PPP made crucial inroads in the Punjab and Sindh provinces, whereas NAP-Wali gained momentum in KPK (former NWFP) and Balochistan.

The Bengali nationalist party, the Awami League (AL), rose to become a major force in former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

The trend was reinforced in the results of the 1970 election in which Bhutto’s PPP swept Punjab and Sindh, NAP-Wali bagged a number of seats in KPK and Balochistan, and AL won 98 per cent of the seats in East Pakistan.

The Mazdoor Kisan Party (MKP) refused to take part in the election. Inspired by the beginning of the Maoist Naxalite guerrilla movement in India and Mao’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China, MKP activists, led by former NAP leader and Pushtun Maoist, Afzal Bangash, traveled to Hashtnagar in KP’s Charsadah District and began to arm and organise the peasants against the local landlords.

MKP’s manoeuvres in this respect were highly successful as its activists joined the area’s peasants and fought running gun battles with the mercenaries hired by the landlords and against the police.

As the area of influence of MKP’s struggle grew, another communist, Major Ishaq Mohammad, joined MKP with his men.

Unlike Bangash and most MKP cadres, Ishaq and his men were not from the KPK. They were from the Punjab.

Ishaq had been a Major in the Pakistan Army before he was jailed and dismissed after he had taken part in an abortive coup attempt against the government of Liaquat Ali Khan in 1951.

The coup attempt that was headed by General Akbar Khan was planned in league with the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP). It was nipped in the bud and its main leaders were all arrested and jailed.

Both men led MKP to spread its influence across various rural and semi-rural areas of the KPK and gained the support of the area’s peasants and as well as some tribal elders.

MKP’s guerrilla activities continued to grow and gather support and their fighters even managed to ‘liberate’ some lands by ousting the landlords.

MKP fighters with their Pushtun peasant army were gaining ground when after a Civil War, East Pakistan broke away and became the independent state of Bangladesh in 1971.

Angry officers of the Pakistan army, who blamed General Yayah Khan (who had replaced Ayub in 1969) for the break-up, invited Bhutto’s PPP to form the government of what remained of Pakistan.

The PPP enjoyed a majority at the centre and in Punjab and Sindh Assemblies, whereas NAP-Wali was able to form coalition governments in KPK (with JUI) and in Balochistan.

Relations between the pro-Soviet Pushtun nationalist and chief of NAP-Wali, Wali Khan, and the pro-China Bhutto, were anything but cordial.

Scholar and historian, Ishtiaq Ahmed, who was a friend of Afzal Bangash, suggests that in a secret meeting between the MKP leadership and Bhutto, Bhutto assured that his government will not take action against MKP guerrillas in KPK that was now under the rule of the NAP-Wali coalition government.